|

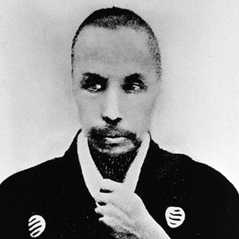

Shozan Sakuma

|

Fujiyama Dojo P.O. Box 20003 Thorold, ON, Canada L2V 5B3 (905) 680-6389 |

|---|

On a warm day in the month of July in Kyoto, in the year 1864, a rider dressed in formal attire approached the Sanjo-kiya-cho district followed by a few retainers. He rode his horse without haste, and carried himself with elegance and quiet dignity, but to the eyes of the onlookers the most conspicuous feature on this rider was his saddle, an excellently crafted European saddle. At a time in which anti-foreigner sentiments ran rampant among the Japanese people, the sight of a samurai riding on an European saddle was more than distasteful. It was a challenge.

As the rider reached the Sanjo-kiya-cho district, his retainers were left behind at a considerable distance, and as fate would have it, they made no effort to catch up with him, nor, as strange as it sounds, did they feel any threat from the two men who were following him on foot.

So, when the two men rushed towards the rider at great speed, closing in from behind on both sides of his mount, the retainers were too far away to prevent the attack. The two men drew their swords with great speed, inflicting deep wounds on the rider's thighs. The rider tried to urge his horse forward, but as the first two attackers disappeared on the side streets, two more emerged from each side of the road, one from a sake shop, the second from behind a cart where he had apparently been waiting. Unable to control his horse or draw his sword, the rider could not escape and was cut twice more, this time across his waist and right forearm.

As the rider fell from his mount, bleeding profusely, but still alive trying to defend himself, the second attackers also disappeared through the side streets. Almost instantly, another group (some say four men, some five) seemed to come out of nowhere, swords already drawn, ready to finish him off before he could regain footing. They did the job quite quickly and effectively and they too vanished as swiftly as they appeared.

The rider suffered thirteen wounds, and was dead before his retainers arrived.

He died, it was said, without calling for help. Hidden inside his clothes were a copy of an imperial decree about the opening of the ports to foreign trade, and there lay the reason for the ambush and the assassination.

The rider's name was Shozan Sakuma. And on the day of his death he had tried to meet with a member of the Imperial family for the purpose of explaining his ideas and to seek the Emperor's permission to finally and legally open Japanese ports to foreign trade. He was unable to meet with the member of the Imperial family, and the ambush occurred when Shozan was returning from this failed visit.

The assassins were, as most historians have it, low ranking samurai from the Higo clan (today's Kumamoto prefecture) and Oki clan (Shimane prefecture). The exact facts leading to the assassination are now lost in speculation.

The day following Sakuma Shozan's death a sign explaining the reason for the killing was placed on the main gate of Gion shrine. It read as follows:

"Shozan advocated European studies and maneuvered for the opening of ports to trade. That alone could not be ignored. Further, in conspiracy with the vile Aizu and Hikone clans, he tried to move the Emperor to Hikone. Since he was an evil and heinous traitor, we inflicted just punishment upon him"

Signed by "Imperial Loyalists".

The man.

Sakuma Shozan was born to a samurai family in 1811, of the Matsushiro clan (Province of Shinano). Being the son of a samurai who was also a scholar, he seemed to inherit an extreme thirst for knowledge that drove him to devour every text about Confucianism and become an ardent follower of the teachings of Chu-Tzu.

But comparable to his learning was his arrogance. He was prone to argue with his teachers, including the renowned Sato Issai, and was reluctant to accept any teaching that he considered incorrect, measuring right and wrong using only his own criteria.

In 1839, Shozan opened a school in Edo, and was deeply involved with it, when the news arrived of China's defeat by the British at the end of the Opium War. Shozan could hardly believe it, and the impression that this event left in him was a lasting one. Western technology, he analyzed, was the cause of the defeat of the nation whose wisdom and culture he admired. He became an advocate of building a powerful modern navy and of establishing a national school system to offer everyone an education based on the ethics of Confucianism.

Shozan tried to communicate his ideas to the Shogun's Council of Elders, and used every opportunity to express his views as strongly as he could before friends, or any individual who could make a difference.

He avidly began to research European science, and one of the men he approached for that endeavor was Egawa Tarozaemon, a magistrate of the Aizu clan who was considered to be one of Japan's leading experts in European tactics. Egawa, however, refused to teach him. It took the influence of a high ranked retainer of the Shogunate to convince Egawa to accept the eager Shozan.

In the end, Egawa's reluctance proved to be well founded. Shozan resented the slow pace of the teaching, complained bitterly about why he was not being taught everything at once, and why all knowledge was not being given freely. He was angry and outraged that the teachers kept some important points (Higi, or Secret Techniques) and did not reveal them all from the start. He even wrote a letter to his mother expressing his feelings, and lamenting the endless repetition of drills.1 The ambitious Shozan considered himself to be ready for more, and worthy of all knowledge, and hated the fact that he had to spend time firing guns "like an ordinary man". He was being taught in a proper manner, according to the standards of all classical ryu, but his arrogance and obsessive impatience made him rebel against what he considered to be an obsolete way. On a warm day in the month of July in Kyoto, in the year 1864, a rider dressed in formal attire approached the Sanjo-kiya-cho district followed by a few retainers. He rode his horse without haste, and carried himself with elegance and quiet dignity, but to the eyes of the onlookers the most conspicuous feature on this rider was his saddle, an excellently crafted European saddle. At a time in which anti-foreigner sentiments ran rampant among the Japanese people, the sight of a samurai riding on an European saddle was more than distasteful. It was a challenge.

As the rider reached the Sanjo-kiya-cho district, his retainers were left behind at a considerable distance, and as fate would have it, they made no effort to catch up with him, nor, as strange as it sounds, did they feel any threat from the two men who were following him on foot.

So, when the two men rushed towards the rider at great speed, closing in from behind on both sides of his mount, the retainers were too far away to prevent the attack. The two men drew their swords with great speed, inflicting deep wounds on the rider's thighs. The rider tried to urge his horse forward, but as the first two attackers disappeared on the side streets, two more emerged from each side of the road, one from a sake shop, the second from behind a cart where he had apparently been waiting. Unable to control his horse or draw his sword, the rider could not escape and was cut twice more, this time across his waist and right forearm.

As the rider fell from his mount, bleeding profusely, but still alive trying to defend himself, the second attackers also disappeared through the side streets. Almost instantly, another group (some say four men, some five) seemed to come out of nowhere, swords already drawn, ready to finish him off before he could regain footing. They did the job quite quickly and effectively and they too vanished as swiftly as they appeared.

The rider suffered thirteen wounds, and was dead before his retainers arrived.

He died, it was said, without calling for help. Hidden inside his clothes were a copy of an imperial decree about the opening of the ports to foreign trade, and there lay the reason for the ambush and the assassination.

The rider's name was Shozan Sakuma. And on the day of his death he had tried to meet with a member of the Imperial family for the purpose of explaining his ideas and to seek the Emperor's permission to finally and legally open Japanese ports to foreign trade. He was unable to meet with the member of the Imperial family, and the ambush occurred when Shozan was returning from this failed visit.

The assassins were, as most historians have it, low ranking samurai from the Higo clan (today's Kumamoto prefecture) and Oki clan (Shimane prefecture). The exact facts leading to the assassination are now lost in speculation.

The day following Sakuma Shozan's death a sign explaining the reason for the killing was placed on the main gate of Gion shrine. It read as follows:

"Shozan advocated European studies and maneuvered for the opening of ports to trade. That alone could not be ignored. Further, in conspiracy with the vile Aizu and Hikone clans, he tried to move the Emperor to Hikone. Since he was an evil and heinous traitor, we inflicted just punishment upon him"

Signed by "Imperial Loyalists".

The man.

Sakuma Shozan was born to a samurai family in 1811, of the Matsushiro clan (Province of Shinano). Being the son of a samurai who was also a scholar, he seemed to inherit an extreme thirst for knowledge that drove him to devour every text about Confucianism and become an ardent follower of the teachings of Chu-Tzu.

But comparable to his learning was his arrogance. He was prone to argue with his teachers, including the renowned Sato Issai, and was reluctant to accept any teaching that he considered incorrect, measuring right and wrong using only his own criteria.

In 1839, Shozan opened a school in Edo, and was deeply involved with it, when the news arrived of China's defeat by the British at the end of the Opium War. Shozan could hardly believe it, and the impression that this event left in him was a lasting one. Western technology, he analyzed, was the cause of the defeat of the nation whose wisdom and culture he admired. He became an advocate of building a powerful modern navy and of establishing a national school system to offer everyone an education based on the ethics of Confucianism.

Shozan tried to communicate his ideas to the Shogun's Council of Elders, and used every opportunity to express his views as strongly as he could before friends, or any individual who could make a difference.

He avidly began to research European science, and one of the men he approached for that endeavor was Egawa Tarozaemon, a magistrate of the Aizu clan who was considered to be one of Japan's leading experts in European tactics. Egawa, however, refused to teach him. It took the influence of a high ranked retainer of the Shogunate to convince Egawa to accept the eager Shozan.

In the end, Egawa's reluctance proved to be well founded. Shozan resented the slow pace of the teaching, complained bitterly about why he was not being taught everything at once, and why all knowledge was not being given freely. He was angry and outraged that the teachers kept some important points (Higi, or Secret Techniques) and did not reveal them all from the start. He even wrote a letter to his mother expressing his feelings, and lamenting the endless repetition of drills.1 The ambitious Shozan considered himself to be ready for more, and worthy of all knowledge, and hated the fact that he had to spend time firing guns "like an ordinary man". He was being taught in a proper manner, according to the standards of all classical ryu, but his arrogance and obsessive impatience made him rebel against what he considered to be an obsolete way.

Shozan fully demonstrated his inability to abide by the spirit and tradition of the martial arts when, after he was granted the position of gunnery instructor, the certificates he awarded to his disciples stated "teach your juniors all you know and never be reluctant", disregarding the ethical oath of strict confidentiality that is the trademark of such documents.

Still, Shozan did not lack intelligence. At a very fast pace he began to study Dutch in order to study European science books in their original language2, as well as every available text in military science and gunnery. He managed with very little sleep and did away with most social amenities, but by 1850 he had opened his own specialized gunnery school, and by then he had been able to construct a seismometer, an apparatus to measure the density of metal for the proper forging of gun barrels, designed an electric medical instrument, cast a replica of a European bronze cannon, etc.

His motto was "Toyo dotoku. Seiyu geijutsu" (Eastern ethics. Western techniques") and some of his students went on to become prominent figures in the history of Japan, such as Sakamoto Ryoma and Nakaoka Shintaro.

Shozan's passion brought him into difficulties when, in 1853, a squadron of warships under the command of Commodore Perry arrived in Japan, and Shozan, convinced that Japan should send its brightest men to the West to learn more about it, advised one of his disciples, Yoshida Shoin, to stow away in one of the ships in order to get to America and learn about American culture, form of government, industry, etc.

Such an action was prohibited by Japanese law and punishable by death. Regardless, Shoin and another young man attempted to get on board a ship when Perry returned the following year. They were refused, and when under the custody of Japanese authorities, a farewell poem, written by Shozan, was found on Shoin.

Shozan was arrested as the instigator of the crime, but he behaved as arrogantly and defiantly as ever, and brought himself very close to the penalty of death or life imprisonment.

Once again, the intervention of a high-ranked retainer of the Shogunate placed him in a more favorable situation. He was sentenced only to home confinement. It would last more than eight years, but Shozan used them by continuing his studies, and writing the famous "Seikenroku" (Reflections on My errors), which was far from an apology, but rather another exposition of his motives and ideas about importing foreign technology, and the opening and modernization of Japan.

Shozan became free again in 1862. By then Japan had seen many changes in its internal affairs and the conditions of the country were severe. The anti-foreign sentiments were as strong as ever, if not worse. The Shogunate was in crisis, and was seeking the Emperor's approval for the commerce treaty with the United States arranged by Chief Minister Ii Naosuke.3 But the Emperor, in Kyoto, was surrounded by xenophobic royalists who opposed the idea of opening the country.

Shozan began to ask for the backing of prominent retainers of the Aizu and Hikone clans, among whom he had friends, who although supporters of the Shogunate, could make his position before the Emperor stronger.

It must be noted that the viewpoints about the opening of Japan among the members of Aizu and Hikone clans were also divided, and the responses were not always favorable. Internal conflicts within the clans made his request a very difficult one.

He wrote many letters expressing his views, always emphasizing that the only solution to the country's conflicts was to move the Imperial court to Hikone Castle, under the protection of the Shogunal government forces, where a reconciliation between the Emperor and the Shogunate could take place much more quickly, bringing about the legal opening of the ports.

Eventually he received the backing he sought and he made the proposal to the government (he also visited Kyoto, trying to convince the Imperial Family and some nobles to take heed, and hear his proposal) but with it, came letters of warning from some of the clans members who might or might have not agreed with his views, but respected his fiery militancy. The warnings were well founded, since Shozan's ideals were gaining him many dangerous enemies who labeled him a traitor.

Ignoring the warnings, Shozan adopted the custom of using a European saddle that further irritated those who disagreed with his views and despised his arrogance He death came as a logical conclusion. Shozan fully demonstrated his inability to abide by the spirit and tradition of the martial arts when, after he was granted the position of gunnery instructor, the certificates he awarded to his disciples stated "teach your juniors all you know and never be reluctant", disregarding the ethical oath of strict confidentiality that is the trademark of such documents.

Still, Shozan did not lack intelligence. At a very fast pace he began to study Dutch in order to study European science books in their original language2, as well as every available text in military science and gunnery. He managed with very little sleep and did away with most social amenities, but by 1850 he had opened his own specialized gunnery school, and by then he had been able to construct a seismometer, an apparatus to measure the density of metal for the proper forging of gun barrels, designed an electric medical instrument, cast a replica of a European bronze cannon, etc.

His motto was "Toyo dotoku. Seiyu geijutsu" (Eastern ethics. Western techniques") and some of his students went on to become prominent figures in the history of Japan, such as Sakamoto Ryoma and Nakaoka Shintaro.

Shozan's passion brought him into difficulties when, in 1853, a squadron of warships under the command of Commodore Perry arrived in Japan, and Shozan, convinced that Japan should send its brightest men to the West to learn more about it, advised one of his disciples, Yoshida Shoin, to stow away in one of the ships in order to get to America and learn about American culture, form of government, industry, etc.

Such an action was prohibited by Japanese law and punishable by death. Regardless, Shoin and another young man attempted to get on board a ship when Perry returned the following year. They were refused, and when under the custody of Japanese authorities, a farewell poem, written by Shozan, was found on Shoin.

Shozan was arrested as the instigator of the crime, but he behaved as arrogantly and defiantly as ever, and brought himself very close to the penalty of death or life imprisonment.

Once again, the intervention of a high-ranked retainer of the Shogunate placed him in a more favorable situation. He was sentenced only to home confinement. It would last more than eight years, but Shozan used them by continuing his studies, and writing the famous "Seikenroku" (Reflections on My errors), which was far from an apology, but rather another exposition of his motives and ideas about importing foreign technology, and the opening and modernization of Japan.

Shozan became free again in 1862. By then Japan had seen many changes in its internal affairs and the conditions of the country were severe. The anti-foreign sentiments were as strong as ever, if not worse. The Shogunate was in crisis, and was seeking the Emperor's approval for the commerce treaty with the United States arranged by Chief Minister Ii Naosuke.3 But the Emperor, in Kyoto, was surrounded by xenophobic royalists who opposed the idea of opening the country.

Shozan began to ask for the backing of prominent retainers of the Aizu and Hikone clans, among whom he had friends, who although supporters of the Shogunate, could make his position before the Emperor stronger.

It must be noted that the viewpoints about the opening of Japan among the members of Aizu and Hikone clans were also divided, and the responses were not always favorable. Internal conflicts within the clans made his request a very difficult one.

He wrote many letters expressing his views, always emphasizing that the only solution to the country's conflicts was to move the Imperial court to Hikone Castle, under the protection of the Shogunal government forces, where a reconciliation between the Emperor and the Shogunate could take place much more quickly, bringing about the legal opening of the ports.

Eventually he received the backing he sought and he made the proposal to the government (he also visited Kyoto, trying to convince the Imperial Family and some nobles to take heed, and hear his proposal) but with it, came letters of warning from some of the clans members who might or might have not agreed with his views, but respected his fiery militancy. The warnings were well founded, since Shozan's ideals were gaining him many dangerous enemies who labeled him a traitor.

Ignoring the warnings, Shozan adopted the custom of using a European saddle that further irritated those who disagreed with his views and despised his arrogance He death came as a logical conclusion.

Traitor or Visionary?

In 1872, with the Meiji era already in progress, the modern educational system began in Japan and trains ran between Shimbashi and Yokohama. Japan went on to construct a powerful navy, and patterned its navy and armed forces after its Western counterparts; Western technology was adopted, and even European clothing styles and dishes were "borrowed" and became part of everyday life. By 1890 the Imperial Diet was formed, becoming Japan's first parliament...and more. Could those changes be what Shozan envisioned? Would Sakuma Shozan have approved of the new Japan? Is "Toyo dotoku. Seiyo geijutsu" a valid motto today? Depending on whom you ask, Shozan is described either as a traitor or a man of vision, according to what they believe that Japan has gained or lost forever. We are, of course, free to draw our own conclusions, but if he were still among us, it is our belief that he would still strive to learn more and more, would hold his opinions to be the right ones, and would continue challenging others by riding his European style saddle, stubbornly and arrogantly until the very end of time. 1. Which he considered to be a waste of time. 2. Most of the materials accessible to him would have been in Dutch. 3. Done without Imperial consent. Assassinated in 1860. The events surrounding his death are known as "The Sakuradamongai Incident". |

|---|